Translate this page into:

Determining the utility of peer-assisted learning to enhance clinical skills at the bedside in a Postgraduate Homoeopathic Institute

*Corresponding author: Bipin Sohanraj Jain, Principal, Professor and Head, Department of Homoeopathic Materia Medica, Dr. M. L. Dhawale Memorial Homoeopathic Institute, Palghar, Maharashtra; Director, Academics, Dr. M. L. Dhawale Memorial Organizations, Maharashtra, India. drjainbipin@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Jain BS. Determining the utility of peer-assisted learning to enhance clinical skills at the bedside in a Postgraduate Homoeopathic Institute. J Intgr Stand Homoeopathy 2020;3(2):29-36.

Abstract

Objectives:

Despite considerable clinical material in hospitals, students often cannot hone their bedside skills; these skills need continuous practice and input from teachers and medical officers (MOs). Making such inputs frequently available to students in busy wards and casualties is very demanding. We, therefore, conducted this study to explore the utility of peer-assisted learning (PAL) as an alternative to enhance students’ clinical skills at the bedside in a Postgraduate Homoeopathic Institute. This study was conducted at a 100-bedded Homoeopathic PG institute hospital with a 24-h emergency ward where various clinical conditions and emergency cases are treated. The objectives of the study were to study the role of PAL in enhancing clinical skills in terms of receiving the patient, history taking, clinical examination, and developing collaborative and constructive practices at the bedside and exploring the role of PAL in developing a conducive atmosphere of learning and to enhance sensitivity to peers.

Materials and Methods:

An orientation session and checklist were created after input from MOs and through a pilot study of 25 Part one senior. The students were educated regarding the concept and were asked to take up one case every week to observe and discuss each other’s clinical skills for 12 weeks with the help of a checklist. A retrospective pre-questionnaire was used to analyze the enhancement of clinical bedside skills. The MO analyzed these using the same questionnaire and collectively analyzed student performance at the end of 12 weeks.

Results:

Student responses were evaluated statistically using the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test (P ≤ 0.05). The results revealed a significant change in history-taking attitude, history-taking skills and knowledge, examination skills, investigation correlations, interpersonal relationships, and learning atmosphere.

Conclusion:

The process of PAL enables student physicians to improve their clinical knowledge, skills, and attitude along with interpersonal relations. This process also enables collaborative and constructive learning and improves students’ sensitivities, allowing them to learn from each other.

Keywords

Peer-assisted learning

Clinical skills

Bedside

Collaboration

Constructive

Homoeopathic

INTRODUCTION

The most critical need of medical education is to create a conducive and open learning circumstance for enhancing the student physician’s clinical skills at the bedside, with the availability of an observer and a guide in real-time. All knowledge gained in the classroom loses its utility if not applied in the clinical setup. Doctor-teachers bear the responsibility for clinical teaching, which includes providing guidance at the bedside. This improves the student physician’s skills and attitudes while enabling them to integrate knowledge acquired from different sources.

However, patients can visit the hospital at any time, and in any situation, teachers may not always be available in real-time and circumstances. Student physicians need someone who is readily available round the clock, easily approachable, and equally connected with the subject and floor practices. Such a guide can help in evolving a system of mutual collaborative learning and constructive practice. This enables both the learner and guide to benefit through enhanced skill, improved attitude, a deeper understanding of the operational application of knowledge. The easiest and most readily available guide for a student physician who can potentially fulfill all the above-mentioned criteria is another student physician, a peer. We, therefore, planned a learning project to explore the operational utility of the concept and practice of peer-assisted learning (PAL), and understand if it had any practical utility in real-world clinical situations.

Background study

Wards are often full of patients; unfortunately, for the medical student to find a teacher doctor who can provide guidance in learning and enhancing skills is difficult.[1] To have a colleague who can serve as a teacher and compatriot for gathering and noting evidence can be extremely convenient and fulfilling. Hence, learning from one’s colearner and immediate seniors has become popular. The process is called PAL, defined as “people from similar social groupings who not professional teachers are helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching.”[1] Collaborating with colleagues at the bedside not only builds and improves one’s confidence in communication with others but also improves bedside and patient examination skills.[2] Teaching guided by peers is an effective method to harness skills; this further validates the benefits of engaging with peers. Getting evaluation from colleagues or peers forms one of the important parts of learning and is an important component of PAL.[3]

There are multiple benefits of PAL: Primarily, it helps to enhance good practices and correct mistakes. Without the presence of a teacher doctor, it is difficult to enhance skills related to history taking and performing bedside examination. Evaluation by peers can help in assessing the performance at three levels:

What was performed well?

What was not performed well?

How can the deficient areas be improved next time?

PAL can help the one providing input and the one receiving it, as both need to use all their faculties in improving their functioning. This enables direct objective input on performance at the bedside.[4]

Existing literature also emphasizes the participation of peer’s in enhancing bedside skills. They also hint at the developing of values and relationships and also suggest the guidelines for achieving it.[1-8]

Context of the study

The study was conducted in a Dr. M. L. Dhawale Memorial Homoeopathic Institute’s (MLDMHI) 100-bedded teaching hospital Rural Homoeopathic Hospital (RHH), Palghar that has major specialties. The hospital functions in a predominantly rural area. It also has a rural and tribal cottage hospital dedicated to training the students in clinical skills at the bedside.

Medical officers (MOs) and other RMOs, although available, are often extremely busy and cannot address students concerns and monitor their training. Students often do not follow the standard processes in History Taking and Clinical Examination or engage in collaborative learning due to work-related stress and poor interpersonal skills. The MOs cannot always observe and correct these processes. Therefore, the PAL system was designed to understand the outcome of collaborative learning and its practical application in improving the learning atmosphere for student physicians.

Objectives

The objectives are as follows:

Studying the role of PAL in enhancing clinical skills in terms of receiving the patient, history taking, and bedside clinical examination

Studying the role of PAL in developing collaborative and constructive practices at the bedside to learn from peers

Exploring the role of PAL in developing a conducive atmosphere of learning and enhance sensitivity to peers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All the 25 students from the Junior MD (Hom) Part I batch at MLDMHI who were admitted in December 2016 and doing their house posts were available for the project from March 1, 2017, to May 31, 2017, and were included in the study.

Methodology

Research design

Pre-experimental.

Sampling

Non-probability sampling: All the students of the batch were involved.

Inclusion criteria

All the part one junior MD (Hom) students were include in the study.

Exclusion criteria

None.

Creating the checklist

A checklist was created for observation and discussion on bedside clinical skills based on input from the MO. A pilot study was undertaken with MD Part I senior students, and the checklist was thus refined through their inputs covering the following six main domains.

Receiving the patient

History taking attitude

-

History taking skills and knowledge

Chief complaint

Associated complaints

History and habits

Personal history.

Examination Skills

Correlation with Investigations

Interpersonal skills with patients.

Orientation and sensitization of students and MOs

This was conducted to determine and address the participants’ sensitivity and biases regarding the project objectives and checklist.

Clinical bedside observation

The students were asked to observe their peers’ bedside clinical skills, provide inputs based on the checklist points, and conduct discussions among themselves. They were advised to consecutively change roles so that each student could observe and take 12 cases, respectively. One case per week, per student, for 12 weeks was planned. A total of 300 cases were observed and taken.

Input from 4 MOs about the cumulative functioning of the students

This was taken at the end of the project using a retrospective pre-questionnaire based on receiving the patient, history taking skills, examination skills, interpersonal relationships, and learning atmosphere.

Evaluation questionnaire

The students’ final inputs were obtained regarding their own functioning through a retrospective pre-questionnaire. The final outcome of the project was determined through the evaluation of the questionnaire.

Outcome assessment

All the forms and retrospective pre-questionnaires were studied for change in the following domains:

Receiving the patient

History taking attitude

History taking skills and knowledge

Examination skills

Investigation correlations

Interpersonal relationships and learning atmosphere.

Each domain was further coded based on the evaluation criteria [Appendix]; all domains were evaluated individually and collectively for pre- and post-assessment. Final analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon-matched pairs signed-rank test for the retrospective pre-questionnaire.

Method of assessment

Post-test analysis

Qualitative data, non-parametric test, and Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test.

RESULTS

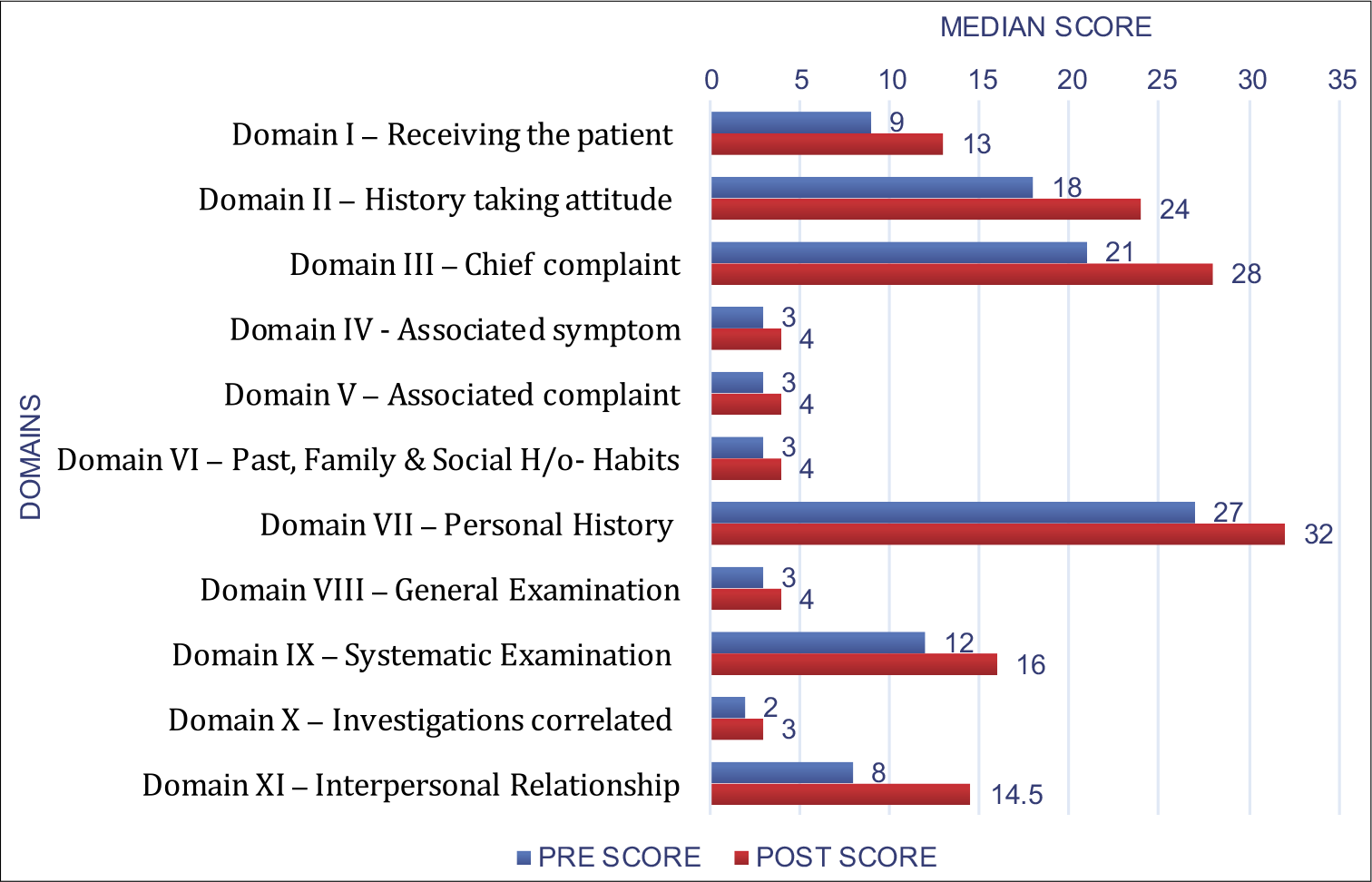

Twenty-five PG students participated in the project; all of them filled the retrospective pre-questionnaire. The questionnaire has 11 domains (Annexure I). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) [Graph 1].

- Transverse comparative bar graph to represent the comparative aspect in each domain.

As the collected data were in ordinal measurement, the pre-post analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All results were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test based on negative ranks.

Students could change the approach to receiving the patient [Table 1], especially through introducing themselves and explaining the purpose for the interview rather than starting the history taking abruptly. There was also a change in addressing the patient and making the patient comfortable. PAL enabled the students to follow these processes from often to always in most of the cases.

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Sig.(two-tailed)P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE RP | 9.40 | 2.12 | 9.00 | ‒4.317b | 0.000** |

| POST RP | 13.20 | 1.68 | 13.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

In history taking [Table 2], major changes were observed at level of organization of the interview, explaining the next step to the patient, and providing assurances to the patient, which indicated improvement of affective skills.

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Sig(two-tailed)P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE HT | 18.60 | 4.311 | 18.00 | –4.206b | 0.000* |

| POST HT | 24.04 | 2.669 | 24.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

In chief complaints, there was significant change while asking the course of illness [Table 3], onset – duration – progress, modifying factor/s, negative data, and causative factor/s.

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Si(two-tailed P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE CC | 21.24 | 4.558 | 21.00 | –3.929b | 0.000** |

| POST CC | 26.80 | 2.345 | 28.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

Associated symptoms and associated complaints were inquired more frequently [Table 4].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. S(two-tail P valu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE AS | 2.92 | 1.038 | 3.00 | –3.419b | 0.001* |

| POST AS | 3.52 | 0.714 | 4.00 | ||

| PRE AC | 2.96 | 0.978 | 3.00 | –3.606b | 0.000* |

| POST AC | 3.48 | 0.714 | 4.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

Medical history and family history were more frequently noted [Table 5].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th (Median) | Z | Asymp. Sig(two-tailed)pvalue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE PFSH | 2.92 | 0.702 | 3.00 | -3.704b | 0.000* |

| POST PFSH | 3.72 | 0.458 | 4.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

Most of the areas showed a marginal change, but the current mental state and especially the sex area inquiry showed significant change [Table 6].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Sig. (two-tailed) P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE PH | 25.68 | 4.922 | 27.00 | –4.166b | 0.000* |

| POST PH | 30.16 | 2.609 | 32.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

Most systemic examinations were performed more frequently to always; a specific improvement was noted in performing percussion [Table 7].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(Median) | Z | Asymp. Si(two-taile P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE GE | 2.92 | 0.909 | 3.00 | –3.827b | 0.000* |

| POST GE | 3.76 | 0.436 | 4.00 | ||

| PRE SE | 12.20 | 3.291 | 12.00 | –3.426b | 0.001* |

| POST SE | 15.12 | 1.301 | 16.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

While collecting the information, establishing correlations between the examination and investigation results improved and was done more frequently [Table 8].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Sig(two-tailed)P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE INV | 2.48 | 0.872 | 2.00 | –3.694b | 0.000* |

| POST INV | 3.40 | 0.645 | 3.00 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

Major changes were seen in interpersonal relationships; all the criteria show substantial change at all levels. PAL was found to lead to a significant change in communication with peers, along with an increased ability to receive and give assistance. It had also increased the students’ ability to learn from their peers [Table 9].

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 50th(median) | Z | Asymp. Sig(two-tailed P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE IPR | 9.08 | 4.272 | 8.00 | –4.024b | 0.000* |

| POST IPR | 13.79 | 2.303 | 14.50 |

Wilcoxon sign ranked test significant at P ≤ 0.05

MOs

Four MOs who were managing the batch on the floor were asked to rate the performance of the batch [Table 10].

| Pre-test | Post-tes | |

|---|---|---|

| OA | 89 | 117 |

| RH | 94 | 134 |

| VRG | 79 | 106 |

| RD | 84 | 119 |

They further validated the finding of the retrospective pre-questionnaire of the students that PAL had significantly changed the performance of the students on the floor in all areas of knowledge, skills, and attitude as per the checklist form.

DISCUSSION

The problem of enhancing bedside skills was evaluated through peer participation and application of the PAL in this project.

The analysis of the responses obtained using the questionnaire clearly showed that PAL helped in attitudinal change at the level of addressing the patients as well as introducing and making them comfortable on a regular basis rather than infrequently. There was a change in addressing patient concerns by assuring and directing them to the next step. The change was also observed in skills and knowledge in terms of organization of history-taking; the chief complaints were regularly taken after PAL in a more systematic manner and covered all major areas of onset, duration, and progress along with the modifying and causative factors. Negative data were more frequently enquired to form a better clinical sense, along with associated symptoms. Medical history and family history, along with personal complaints, were more frequently inquired into; data about current mental state and sexual history formed the major shift in pre- and post-study evaluation.

A significant change was observed in the general examination and systemic examination. Correlation with the investigation had become an active process in evaluating the history and examination findings.

The student’s knowledge and practice of history receiving and clinical examination also became more systematic and regular, which helped them understand the patient’s state in a holistic way. This also validates the finding from the literature that collaborating with colleagues at the bedside not only builds and improves confidence in communication with others but also improves bedside skills and patient examination skills.[1-4]

Having peers to participate in learning circumstances enhanced the knowledge, skills, and attitude of the medical students; this also helped develop collaborative learning, and enabling each student to develop into a better clinician. In this study, we found that the exercise enhanced the participant’s sensitivity to communicate with peers in active clinical postings. The combination of attitude as a learner who is sensitive to learning from peers or colleagues and collaborating for constructive learning lays the foundation to become a lifelong learner. These values are important to inculcate in student life; the process involves respecting and learning from each other. This process can lay down the foundation of lifelong learning and collaborative learning along with training of budding teachers in medical colleges.

Overall, the process of PAL has definitely helped the group of participant students in a significant way to form the system for continuous clinical training at the bedside, even during odd hours and busy in-patient department.

Promoting PAL can go a long way in the shaping of a value-based, collaborative, and mutually respectful future medical generation by structuring a peer-based teaching learning system.

All systems have their advantage and disadvantages, especially if they are not planned and structured in a proper manner. This practice does not replace teachers but helps to develop future teachers and value-based clinicians. The responsibility of teachers also increases in needing to plan the system, implement it, and takes the time to evaluate the outcome of this PAL.

CONCLUSION

The PAL system enhances:

Acquisition of clinical skills such as receiving the patient, history taking, and clinical examination at the bedside

Development of collaborative and constructive practices at the bedside to learn from peers

Development of a conducive atmosphere of learning and enhancing sensitivity to peers

Development of continuous clinical training at bedside even during the absence of faculty.

Recommendations

It is thus recommended to commence these practices on a regular basis by formulating a proper system and organize its supervision and timely evaluation. This will fetch maximum benefits from the available clinical material to enhance clinical skills at the bedside. This project focused only on assistance at the bedside; however, the system and its practices can be extended to other areas of health-care education, such as enhancing patient care and in carrying out formative assessments. The concept of the observer is not foreign to us. Hence, to have an external observer to enhance learning can be a boon to a homeopath.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to the Faculty of MET, MUHS, for its guidance in understanding the principles of Education Technology during the Advanced Training workshop and Dr Kumar Dhawale for his valuable suggestions in preparing the manuscript. The Research Department, MLDMHI, has given invaluable assistance in the statistical analysis and organizing the findings in its current form. This research paper is based on the project conducted, as a part of the advance education technology course conducted by MUHS Nashik.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. High Educ. 1996;32:321-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Helping each other to learn-a process evaluation of peer assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Are fourth-year medical students effective teachers of the physical examination to first-year medical students? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:177-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twelve tips for medical students to make the best use of ward-based learning. Med Teach. 2017;39:1119-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: Cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynaecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1444-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learning through reflection: The critical role of reflection in work-based learning (WBL) J Work Appl Manag. 2015;7:15-27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34:e102-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

APPENDIX

| Preliminary data | Taken | Not taken | Partially taken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specify which part missed | |||

| History taking | |||

| Chief complaints | |||

| Course of illness | |||

| Onset | |||

| Duration | |||

| Progress | |||

| Modifying factor | |||

| Negative data | |||

| Causative factor | |||

| Associated symptoms | |||

| Associated complaints | |||

| Past medical history | |||

| Patient on medications | |||

| Past history | |||

| Family history | |||

| Social history with habit | |||

| Personal history | |||

| Appetite | |||

| Thirst | |||

| Stool | |||

| Urine | |||

| Sleep and dream | |||

| Current mental state | |||

| Sex | |||

| Menstrual and pregnancy data | |||

| General examination | |||

| Systemic examination | |||

| Inspection | |||

| Palpation | |||

| Percussion | |||

| Auscultation | |||

| Investigation correlated | Done | Not done | Partially done |

| Interpersonal skill | |||

| Addressed patient properly | |||

| Introduced himself and observer to patient | |||

| Explained the purpose | |||

| Made patient feel comfortable | |||

| Allowed patient to talk without much of interference | |||

| Conducted the interview in organized way | |||

| Maintained good eye to eye contact | |||

| Avoided medical jargon | |||

| Provided assurance to patient | |||

| Explained next step to patient | |||

| Showed empathetic attitude to patient | |||

| Organization of inquiry | |||

| Any other observation |

| Domains | Pre | Post | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely | Some times | Often | Always | Rarely | Some times | Often | Always | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Receiving the patient | ||||||||

| 1. Addressed patient properly (rp1) | ||||||||

| 2. Introduced himself and observer to patient (rp2) | ||||||||

| 3. Explained the purpose (rp3) | ||||||||

| 4. Made patient feel comfortable(rp4) | ||||||||

| History taking | ||||||||

| Attitude | ||||||||

| 1. Allowed patient to talk without much of interference (ht1) | ||||||||

| 2. Conducted the interview in organized way (ht2) | ||||||||

| 3. Maintained good eye to eye contact (ht3) | ||||||||

| 4. Avoided medical jargon (ht4) | ||||||||

| 5. Provided assurance to the patient (ht5) | ||||||||

| 6. Explained next step to the patient (ht6) | ||||||||

| 7. Showed empathetic attitude to the patient (ht7) | ||||||||

| History taking skill and knowledge | ||||||||

| Chief complaints | ||||||||

| Course of illness (cc1) | ||||||||

| Onset (cc2) | ||||||||

| Duration (cc3) | ||||||||

| Progress (cc4) | ||||||||

| Modifying factor (cc5) | ||||||||

| Negative data (cc6) | ||||||||

| Causative factor (cc7) | ||||||||

| Associated symptoms | ||||||||

| Associated complaints | ||||||||

| Past history, family history, social history with habits | ||||||||

| Personal history | ||||||||

| 1. Appetite (ph1) | ||||||||

| 2. Thirst (ph2) | ||||||||

| 3. Stool (ph3) | ||||||||

| 4. Urine (ph4) | ||||||||

| 5. Sleep and dreams (ph5) | ||||||||

| 6. Current mental state (ph6) | ||||||||

| 7. Sex (ph7) | ||||||||

| 8. Menstrual and pregnancy data (ph8) | ||||||||

| Examination skill | ||||||||

| General examination | ||||||||

| Examination skill | ||||||||

| Systemic examination | ||||||||

| Inspection (SE1) | ||||||||

| Palpation (SE2) | ||||||||

| Percussion (SE3) | ||||||||

| Auscultation (SE4) | ||||||||

| Investigation correlated | ||||||||

| Interpersonal relationship | ||||||||

| 1. Communication with peers (IPR1) | ||||||||

| 2. Ability to receive input from peers (IPR2) | ||||||||

| 3. Ability to give input to peers (IPR3) | ||||||||

| 4. Ability to learn from peers (IPR4) | ||||||||