Translate this page into:

Assessing the feasibility of homeopathic interventions for metabolic syndrome: A prospective study

*Corresponding author: Dr. Lizmy Jose, Department of Practice of Medicine, Government Homoeopathic Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India. lizmyajith@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sherin KS, Jose L. Assessing the feasibility of homeopathic interventions for metabolic syndrome: A prospective study. J Intgr Stand Homoeopathy. 2025;8:4-12. doi: 10.25259/JISH_102_2024

Abstract

Objectives:

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a global public health concern closely linked to rising obesity rates. It encompasses metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidaemia and hypertension, significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and type 2 diabetes. The objective of this study was to assess the effect of homoeopathic medicines in managing patients with MetS having high triglyceride (TG) levels and reducing their cardiovascular risk.

Material and Methods:

A non-randomised prospective clinical study was conducted at the outpatient department of Government Homoeopathic Medical College, Kozhikode, with 30 participants fulfilling the diagnostic criteria. The participants were administered homoeopathic remedies based on symptom similarity. All cases were followed up for 6 months from initiating of treatment. The assessment was based on the change in total scores of assessment parameters, changes in the Framingham risk score and atherogenic index before and after treatment analysed using statistical tests.

Results:

A higher prevalence of MetS was noted in men and the 40–50 age groups. Sedentary lifestyles and a family history of diabetes, hypertension and CVD were common among participants. Most participants followed a non-vegetarian diet. Significant positive changes were observed in parameters such as body mass index, waist circumference, TG levels, fasting blood sugar, systolic blood pressure and high-density lipoprotein levels. However, there was no significant improvement in diastolic pressure. The observed reduction in both the Framingham risk score and the atherogenic index of plasma due to the intervention is a significant and promising finding.

Conclusion:

Homoeopathic medicines appeared effective in managing MetS and reducing its cardiovascular risk. While these results are promising, further research is needed to understand the mechanisms involved and establish guidelines for integrating homoeopathic treatments into conventional care for patients with MetS.

Keywords

Atherogenic index of plasma

Cardiovascular risk

Framingham risk score

Homoeopathy

Hypertriglyceridemia

Metabolic syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of risk factors that include insulin resistance, obesity, atherogenic dyslipidaemia and hypertension; it increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke. In India, the prevalence of MetS among adults is 30%, largely due to rising obesity rates, with men being more affected than women.[1] Globally, MetS now affects over a billion people.[2] Factors such as obesity, physical inactivity, poor lifestyle and a middle-to-high socioeconomic status contribute to its increased prevalence.[3]

According to the harmonising definition criteria,[4] MetS is diagnosed when three or more of the following criteria are met:

Central obesity: Waist circumference (WC) in cm [Table 1].

Fasting triglyceride (TG) level: ≥150 mg/dL.

Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level: <40 mg/dL in men, <50 mg/dL in women.

Hypertension: Systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg.

Fasting plasma glucose level: ≥100 mg/dL.

| Men | Women | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| ≥94 | ≥80 | Europid, Sub-Saharan African |

| ≥90 | ≥80 | South Asian, Chinese, and ethnic South and Central American |

| ≥85 | ≥90 | Japanese |

Patients with MetS have a 50–60% higher cardiovascular risk.[5] Its components–hypertension, elevated TG levels and increased plasma glucose–are linked to cardiovascular conditions such as coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and heart failure.[6] High TG levels often signal MetS and indicate increased cardiovascular risk. Patients with TG levels >150 mg/dL should be assessed for other metabolic risk factors.[7]

The Framingham risk score and atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) are tools used to assess cardiovascular risk. The Framingham risk score estimates a person’s 10-year risk of heart attack or stroke.[8]

MetS research faces challenges due to its complexity. The heterogeneity of MetS complicates diagnosis and treatment[9] and a lack of biomarkers hinders early detection. Gene-environment interactions are difficult to understand, as these factors vary widely.[10] The causality between MetS components, such as the role of obesity in other traits, remains unclear.[11] Most research focuses on high-income countries, leaving gaps in the knowledge of diverse populations.[12] In addition, comorbidities complicate research. Overcoming these challenges requires multi-omics approaches, longitudinal studies and more research on diverse populations.

Homoeopathy offers a holistic, individualised approach to managing MetS by addressing underlying causes and promoting overall well-being.[13,14] Homoeopathic remedies may provide relief for conditions such as obesity, hypertension and high cholesterol.[15,16]

Several studies have explored the role of potential benefits of homoeopathic treatment for MetS. Venkatesh’s study found that men were more affected than women, with 50% of cases occurring between ages 13 and 16. Poor diet and inactivity were major triggers. Effective remedies included Calc carb, Pulsatilla, Ferrum met, Antimonium crudum, Baryta carb and Silicea, primarily in 200th potency, which showed satisfactory results.[15] Similarly, Nithin’s 2019 study confirmed the effectiveness of homoeopathy particularly in managing TG level. Research on Berberis vulgaris and its active compound berberine found them promising in addressing MetS components such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, obesity and cardiovascular disease (CVD).[17] However, research in this area remains limited, and existing studies often lack rigorous methodologies.

This study was a preliminary investigation to assess the feasibility of a larger trial on homoeopathic treatment for MetS patients with elevated TGs levels.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

After obtaining ethical committee approval, patients presenting with MetS at GHMC, Kozhikode, were screened based on diagnostic and inclusion criteria. Eligible patients were informed about the study, and written consent was obtained before participation.

Study design

This is a prospective observational study was conducted in the outpatient department (OPD) and inpatient department (IPD) of Government Homoeopathic Medical College (GHMC), Kozhikode, with cases of MetS selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at assessing the feasibility of a larger trial. As the study has no control group, the focus was on recruitment, retention and data collection to inform future research design.

Study Setting

Patients attending the OPD and IPD of GHMC, Kozhikode, were screened. Those who satisfied the inclusion criteria were considered for the study.

Study duration

The duration of study was 1 year, 6 months for a period of enrolment and 6 months for follow-up.

Study population

The study was conducted among both urban and rural populations in Kerala.

Sampling

Sample size

To estimate sample size n, we assumed that, standard deviation (SD) of the differences (s) = 5.19 and the ratio of difference of averages (Δ) = 0.655. Then, for a fixed level of significance a = 0.05, and power 1–b =0.90, the estimated sample size was deemed to be n = 26.39. If the dropout rate (d) is 20%, the final sample size would be N = n/(1–d). This was calculated as N = 32.99 rounded up to 33.[18]

Working case definition (diagnostic criteria)

WC: >90 cm (M), >80 cm (F) (South Asian standard)

TG level: ≥150 mg/dL

HDL-C level: <40 mg/dL (M), <50 mg/dL (F)

Blood pressure: Systolic ≥130 mmHg and diastolic ≥85 mmHg

Fasting blood glucose level: ≥100 mg/dL.

Inclusion criteria

Both sexes, aged 25–65 years

-

TGs level ≥150 mg/dL + any 2 of the following:

WC >90 cm (M), >80 cm (F)

HDL-C level: <40 mg/dL (M), <50 mg/dL (F)

Raised blood pressure: Systolic ≥130 mmHg and diastolic ≥85 mmHg

Fasting glucose level ≥100 mg/dL.

Exclusion criteria

History of CVD

On allopathic medication

Severe illness (e.g., malignancy)

Pregnant women

Recent or chronic alcohol intake

Recent or chronic smoking.

Sampling procedure

The cases were selected using purposive sampling.

Screening methods

Lipid profile: A 1 mL venous blood sample was collected after 12 h of fasting and analysed using an AGAPPE test kit (Agappe diagnostics Ltd., Ernakulam, Kerala, India)

Anthropometric measurements: Height, weight, WC and body mass index (BMI) were recorded

Fasting blood sugar level: A 1 mL venous blood sample was collected after 12 h of fasting and tested using a glucose kit

Electrocardiogram: Conducted in the hospital laboratory

Blood pressure: Measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer.

The study was conducted in both outpatient and inpatient settings at GHMC, Kozhikode. Data collection, recording and assessment were conducted by the investigator. Detailed case documentation was maintained using a standardised record.

Homoeopathic management

The homoeopathic treatment approach followed in this study adhered to the foundational principles of homoeopathy, ensuring a personalised and holistic treatment for each patient. The management process involved several key stages:

Case-taking and initial assessment

Each patient’s case was taken with a focus on the physical and mental-emotional aspects of their health. This included detailed interviews where patients were asked about their physical symptoms, lifestyle, emotional state and psychological history. Particular attention was given to the mental-emotional factors that often accompany MetS, such as stress, anxiety and depression.

Remedy selection

Remedies were selected based on the principle of similimum, where the remedy chosen closely matched the totality of the patient’s symptoms. A careful repertorisation process was employed to identify the most appropriate homoeopathic remedy for each patient. This process was guided by an analysis of the patient’s physical symptoms, emotional state and constitutional type, ensuring the chosen remedy addressed both aspects of health

Prescription and follow-up

Initial prescription: Following the case-taking and repertorisation, an individualised homoeopathic remedy was prescribed, considering factors such as symptom intensity, duration and constitutional type

Follow-up: After each follow-up, the patient’s response was carefully assessed. If no improvement was observed, the case was reassessed and a new remedy was selected, often based on an updated repertorisation. If improvement was noted, patients were administered placebo for further monitoring

Higher potency and modifications: In cases where symptoms reappeared or improvement ceased, the remedy was administered in a higher potency. In the event of persistent aggravation without improvement, the case was a re-evaluated and the remedy modified to ensure the most effective treatment

Acute exacerbations: For acute exacerbations of symptoms, homoeopathic remedies were selected based on the acute totality of symptoms. These remedies were often repeated at more frequent intervals to manage the acute presentation effectively.

Response to treatment

Patient responses were monitored closely at each follow-up, and the treatment plan was adjusted based on their progress. The outcomes were categorised into:

Improvement: Notable reduction in symptoms, both physical (e.g., reduction in blood pressure, improvement in lipid profile) and mental/emotional (e.g., reduction in stress and anxiety)

No improvement: If there was no observed improvement after the first round of treatment, the remedy was reconsidered and the patient was reassessed

Aggravation: If symptoms worsen initially before improving, this was documented as a transient aggravation.

Case examples

Patient 1

A 50-year-old women with MetS presented with elevated TG levels, high blood pressure and symptoms of chronic grief. After thorough case-taking, the remedy Natrum muriaticum was selected, based on her mental-emotional symptoms and physical symptoms. At the follow-up visit, a reduction in mental symptoms and improvement in blood pressure was observed. Subsequently, she was administered placebo.

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man with similar MetS parameters but also reporting anxiety about health. The remedy Sulphur 200 was chosen based on his emotional state and physical symptoms. After 1 month of treatment, the patient reported significant improvement in both his physical and mental health with lower TG levels.

Follow-up period

Follow-ups were initially conducted every 15 days, and then monthly for a period of 6 months. Patients were contacted if they missed two consecutive follow-up appointments and were considered dropouts if they missed 3 consecutive months of follow-ups. However, any dropouts were offered standard care on return, despite being excluded from the study analysis.

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Cardiovascular risk was evaluated using the Framingham risk tool and AIP at 6-month intervals. Patients received dietary advice to avoid high-calorie foods, red meat, saturated fats and oils. Recommendations were also provided to enhance physical activity, manage stress and modify other lifestyle factors.

Research tools

Personal data schedule

A structured format was used to collect demographic and clinical data, including name, age, sex, religion, family history, occupation and associated complaints.

Assessment criteria

MetS component analysis

Scoring was based on standardised criteria, recognising potential refinements in future studies:

WC: Scored according to South Asian standards[19] (international diabetes federation criteria)

TG and HDL-C levels: Scored per the National Centres for Environmental Prediction: Adult treatment panel (ATP) III guidelines[20] (TGs: 0–3; HDL-C: 0–2, sex-specific scoring)

Blood pressure: Scored 0–4 per American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) High Blood Pressure Guidelines.[21]

Fasting plasma glucose levels: Scored using the American diabetes association (ADA) classification[22] (0 for normal, 1 for impaired glucose tolerance, 2 for diabetes).

The potential effectiveness of homoeopathic treatment was assessed through changes in total scores of these components, followed by statistical analysis.

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Outcome measurement

Each case was reviewed at 2–3-week intervals

Outcomes were measured by assessing significant changes in the total scores of WC, TGs levels, HDL-C level, blood pressure and fasting blood glucose before and after homoeopathic treatment

Cardiovascular risk was evaluated using the Framingham risk tool and AIP, with scores compared at 6-month intervals.

While this study follows standardised assessment criteria, we acknowledge the potential for further refinement of scoring systems and assessment methodologies to enhance accuracy and clinical relevance in future research.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the study done was acquired from the ethical committee confined at GHMC, Kozhikode on 23 December 2021 Reference No: IEC/12/23.12.2021/24. No adverse effects were reported during the treatment.

Plan of analysis

The data obtained in this study were analysed primarily using descriptive statistics, with some exploratory inferential analysis, in alignment with the study objectives.

Section 1: Baseline data, including sample characteristics, is presented using tables and figures, summarising frequencies and percentages

Section 2: Changes in total scores of assessment parameters before and after treatment were examined, with trends described using descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied as an exploratory tool, and results are illustrated through figures and diagrams. Cardiovascular risk, assessed through the Framingham score and AIP, was similarly explored using paired t-tests.

The sample size may limit the generalizability of findings. Potential confounding variables were not controlled, which may influence observed trends; these are the some limitations of statistical analysis.

Policy implications

The Institutional Ethical Committee and University Kerala University of Health Sciences (KUHS) clearance are being obtained for the study. Informed written consent is being obtained from the participants. We are ensuring that there is no additional financial burden on the participants. Confidentiality is being rigorously maintained throughout the study.

RESULTS

Thirty cases fulfilling the diagnostic, inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected as the sample for the current study. Each participant underwent homoeopathic case taking, followed by prescription of the homoeopathic similimum based on the totality of symptoms. Pre-treatment and post-treatment data were collected and analysed using appropriate statistical tests. The results are presented in tables and graphs for clarity.

Demographic distribution

Age distribution

As shown in Table 2, the majority of participants(33%) were in the 40-50 years age group, followed by 27% in the 50-60 years group, participants aged 30-40 years constituted 17% and those aged 60-70 years made up 23% of the study population .

| Age in years | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 30–40 | 5 | 17 |

| 40–50 | 10 | 33 |

| 50–60 | 8 | 27 |

| 60–70 | 7 | 23 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Sex distribution

The study population consisted of 30 individuals. Among them, 17 were male (57%) and 13 were female (43%) [Table 3].

| Sex | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 17 | 57 |

| Female | 13 | 43 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Occupation distribution

The majority of participants were daily wage workers (43%), followed by housewives (34%). Teachers accounted for 7%, while engineers and businesspersons made up 3% each. The remaining 10% belonged to other occupations [Table 4].

| Occupation | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Housewife | 10 | 34 |

| Daily wage | 13 | 43 |

| Teacher | 2 | 7 |

| Engineer | 1 | 3 |

| Business | 1 | 3 |

| Others | 3 | 10 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Medicine distribution

Various homeopathic medicines were distributed among the participants. Nux vomica was the most commonly used medicine (18%), followed by Sulphur, Calcarea carbonica, and Pulsatilla (each 13%). Phosphorous and Natrum muriaticum were prescribed to 11% of the participants. Other medicines such as Graphites, Arsenicum album, Lycopodium, Lachesis, Carcinosin, Thuja, and Sepia were each used in 3% of cases [Table 5].

| Medicine | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sulphur | 4 | 13 |

| Nat mur | 3 | 11 |

| Calc carb | 4 | 13 |

| Pulsatilla | 4 | 13 |

| Graphites | 1 | 3 |

| Ars alb | 1 | 3 |

| Nux vom | 5 | 18 |

| Lycopodium | 1 | 3 |

| Lachesis | 1 | 3 |

| Carcinosin | 1 | 3 |

| Thuja | 1 | 3 |

| Sepia | 1 | 3 |

| Phosphorous | 3 | 11 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Inference

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences V20 software (IBM corporation, New York, USA). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test and paired t-tests demonstrated statistically significant differences in several metabolic parameters post-treatment, with P < 0.01 for most variables.

BMI, WC, TG levels, fasting blood sugar levels, HDL-C levels, systolic blood pressure, Framingham risk score and AIP showed significant reductions, indicating possible positive effects of homoeopathic treatment

Diastolic blood pressure did not show significant improvement (P = 0.095)

The reduction in the Framingham risk score and AIP suggests a potential reduction in cardiovascular risk following homoeopathic treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to assess the feasibility of using homoeopathic medicines for managing MetS and reducing cardiovascular risk. Thirty patients aged 25–65 years being treated at the Government Homoeopathic Medical College, Kozhikode, were treated for 6 months with pre- and post-treatment assessments.

The study found the highest prevalence of MetS in the 40–50 age group (33%), followed by 50–60 (27%), 60–70 (23%) and 30–40 (17%). Men (57%) outnumbered females (43%). Many participants were housewives or leading sedentary lifestyles, while others had daily jobs with varying levels of physical activity and stress. Regarding diet, 10% and 90% followed a vegetarian and non-vegetarian diet, respectively. Significant family histories of CVD (43%), hypertension (50%), diabetes mellitus (63%) and cancer (17%) were noted.

Homoeopathic medicines were prescribed based on the totality of symptoms, with Nux vomica (18%) being most effective, followed by Calc carb and Pulsatilla (13%). Potencies used included 30, 200 and 1M, based on homoeopathic principles.

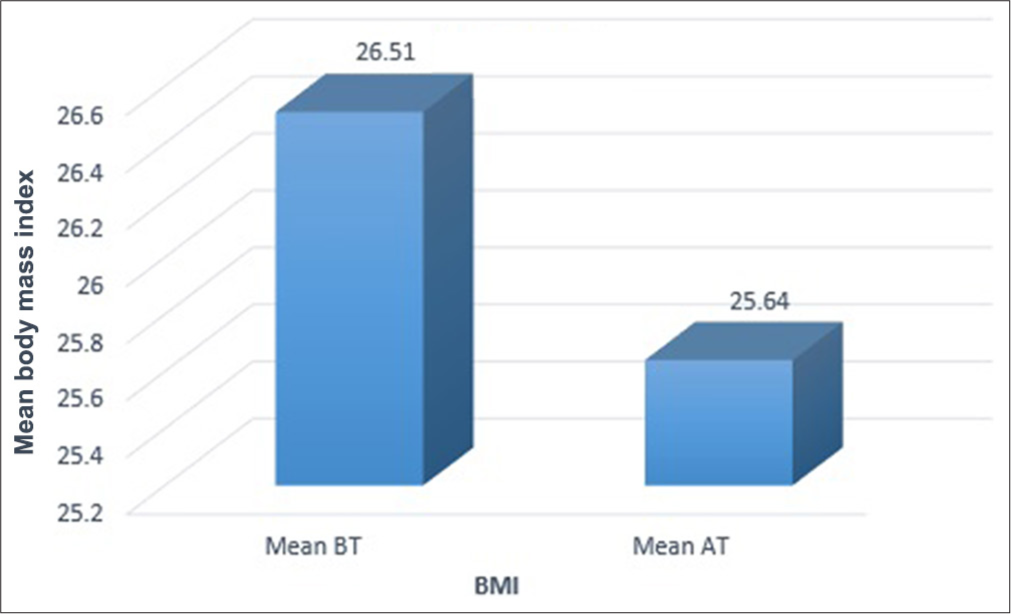

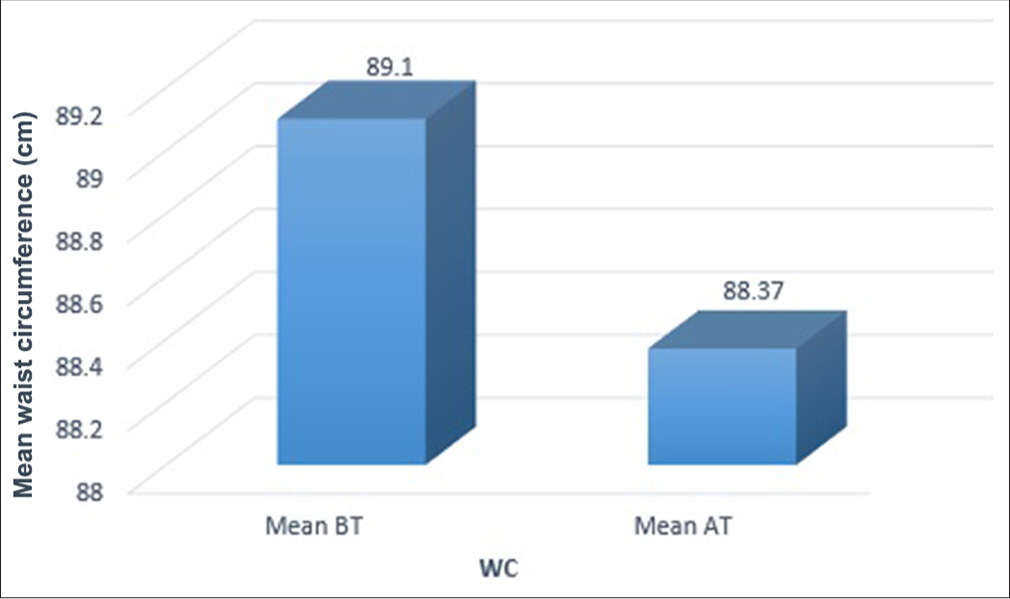

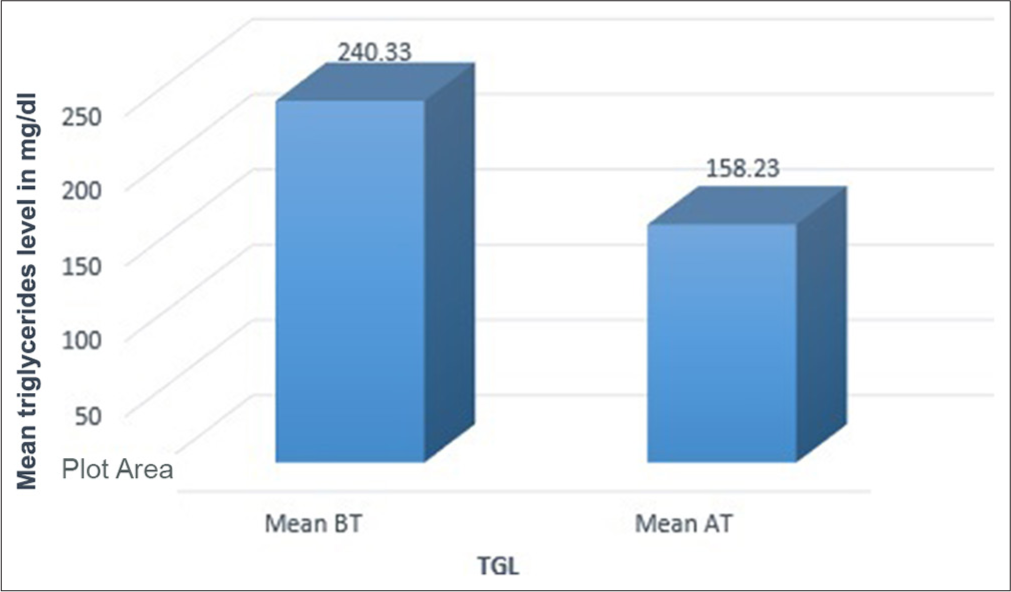

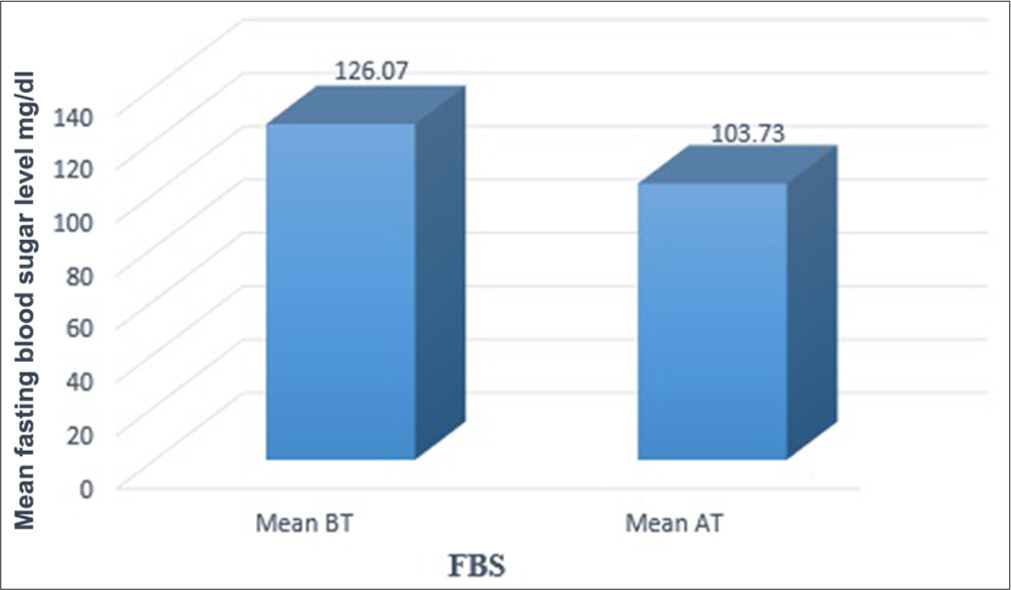

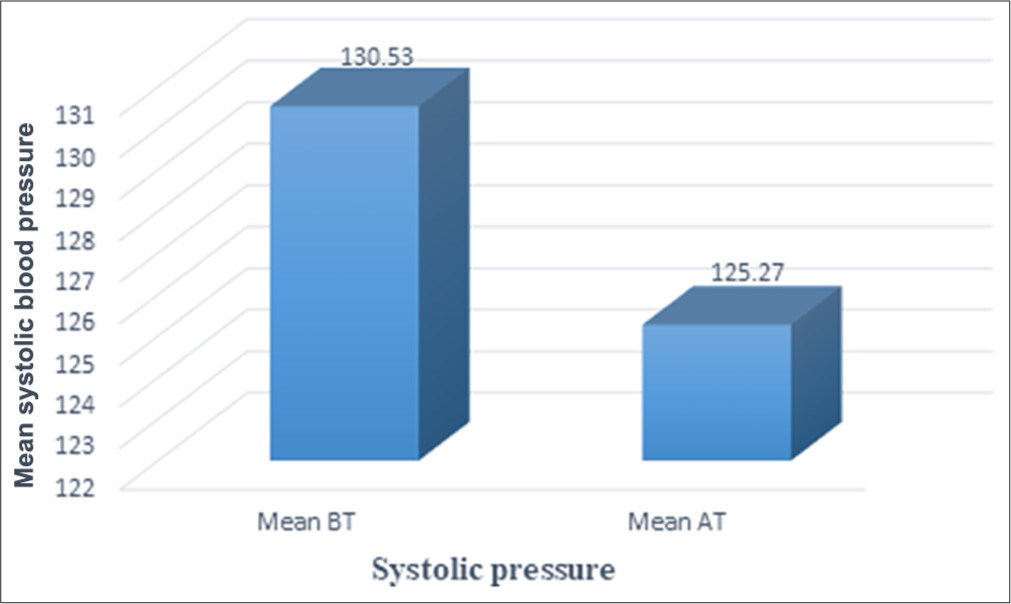

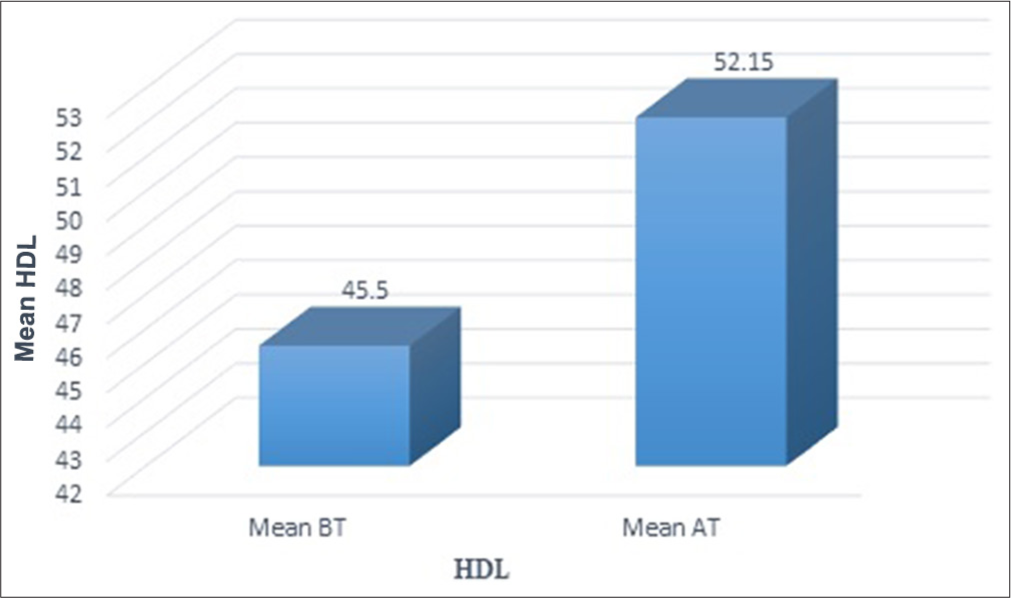

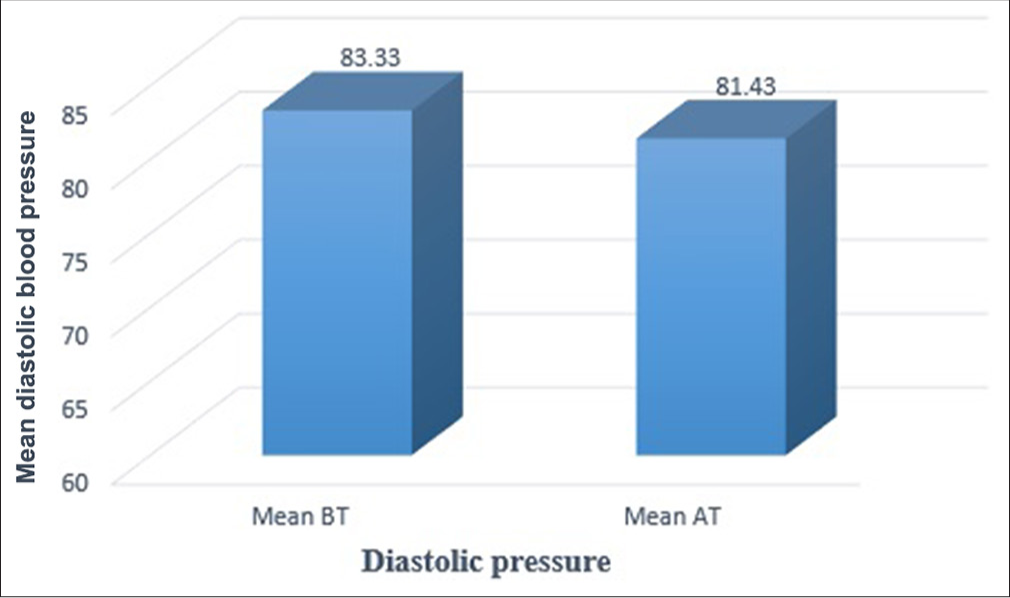

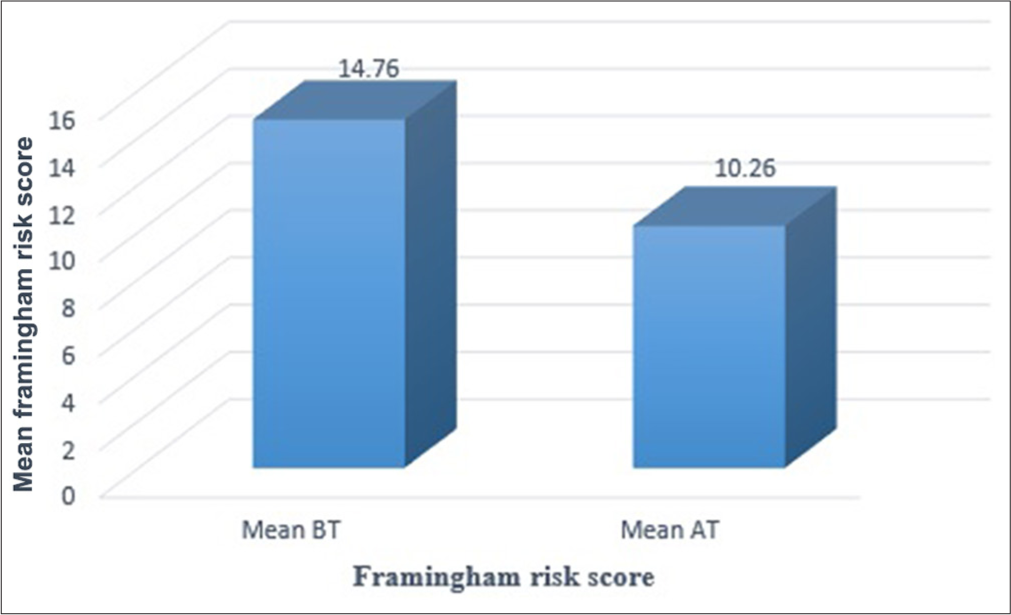

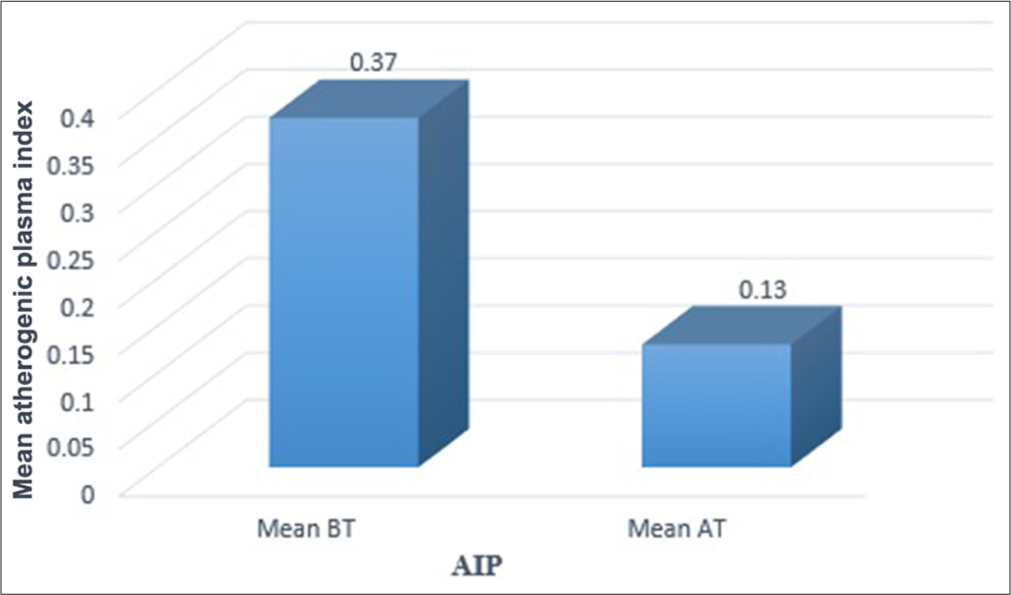

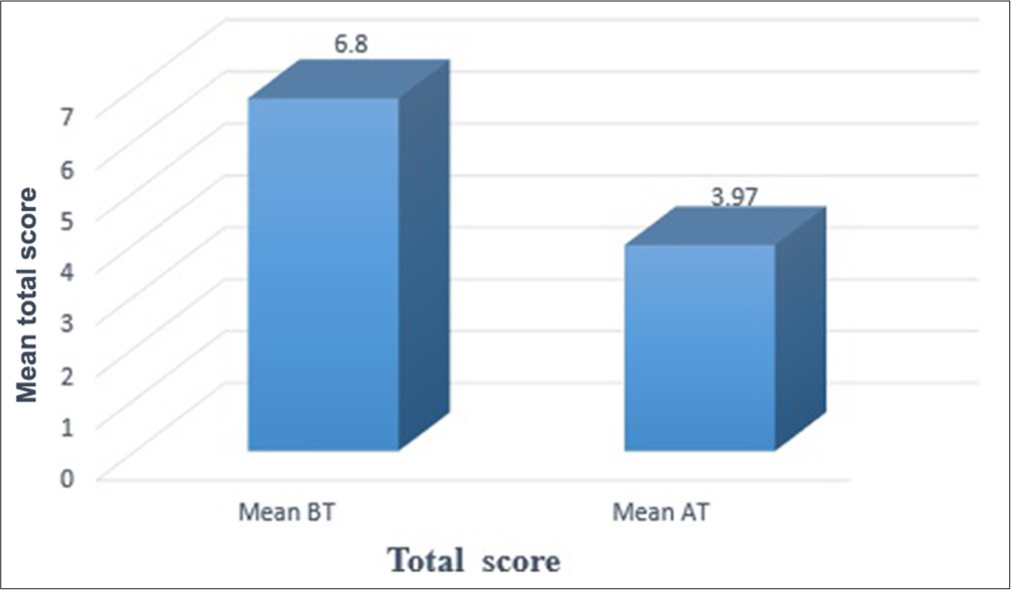

Post-treatment assessments revealed significant improvements in various parameters [Figure 1]. The BMI decreased from 26.51 to 25.64 (kg/m2), WC dropped from 89.10 to 88.37 cm [Figure 2], TG level decreased from 240.33 to 158.23 mg/dL [Figure 3] and fasting blood sugar levels decreased from 126.03 to 103.73 mg/dL [Figure 4]significantly. Systolic blood pressure reduced from 130.53 to 125.27 mmHg [Figure 5], and HDL-C increased from 45.50 to 52.15 mg/dL [Figure 6]. However, no significant change was observed in diastolic blood pressure [Figure 7]. There was also a notable reduction in cardiovascular risk, as measured using the Framingham risk score and AIP [Table 6 and Figures 8 and 9].

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on body mass index. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment, BMI: Body mass index.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on waist circumference. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment, WC: Waist circumference.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on triglycerides. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment, TGL: Triglycerides.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on fasting blood sugar. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment, FBS: Fasting blood sugar.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on systolic pressure. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on high-density lipoprotein (HDL). BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on diastolic pressure. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on Framingham risk score. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment.

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on atherogenic index. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment, AIP: Atherogenic index of plasma.

| Parameter | Mean (before treatment) | Mean (after treatment) | Mean difference | P-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.51 | 25.64 | 0.87 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89.10 | 88.37 | 0.73 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Triglyceride level (mg/dL) | 240.33 | 158.23 | 82.10 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) | 126.07 | 103.73 | 22.34 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130.53 | 125.27 | 5.26 | 0.011 | Significant |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.33 | 81.43 | 1.90 | 0.095 | Not significant |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.50 | 52.15 | −6.65 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Framingham risk score | 14.76 | 10.26 | 4.50 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Atherogenic index of plasma | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.24 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Total score | 6.80 | 3.97 | 2.83 | <0.001 | Significant |

However, several limitations must be considered. The lack of a control group prevented definitive conclusions. The small sample size and short follow-up period (6 months) also limit the study’s generalizability and long-term insights.

This study suggests potential benefits of homoeopathic treatment but requires further research. Future randomised controlled trials (RCTs) should involve larger sample sizes, blinding and a control group. Long-term follow-up and objective clinical measures should be incorporated to confirm the effectiveness and refine treatment protocols.

A diet high in refined carbs, sugars and unhealthy fats contributes to obesity and insulin resistance, key factors in MetS. Food with a high-glycaemic index causes blood sugar spikes, while fibre improves insulin sensitivity. Excess saturated and trans fats worsen inflammation and dyslipidaemia, whereas omega-3s support better lipid profiles. Deficiencies in magnesium and Vitamin D impair glucose metabolism. A sedentary lifestyle reduces insulin sensitivity and increases visceral fat, while stress and poor sleep disrupt hormones, promoting dysfunction. Smoking and excessive alcohol further elevate risks. A balanced diet, exercise, stress management and proper sleep are essential for prevention. Future research should explore lifestyle control strategies such as personalised diets, behaviour changes and tech monitoring to reduce the risk of MetS.

In this study, homoeopathic treatment for MetS was based on the principle of individualisation, treating the person as a whole and considering all aspects of their physical, mental and emotional health. By applying the law of similars and using remedies that correspond to the patient’s unique symptom picture, homoeopathy aims to restore balance in the body and address the root causes of metabolic dysfunction. This holistic approach, combined with personalised remedy selection and an emphasis on the mind-body connection, can guide clinical outcomes by improving metabolic markers and supporting long-term health. In this study, significant improvements were seen in the management of MetS, reducing reliance on conventional medications and enhancing the patient’s overall quality of life. Overall, this study suggests that homoeopathic medicines are effective for managing MetS and reducing cardiovascular risk [Figure 10].

- Graphical representation for the effect of intervention on total score. BT: Before treatment, AT: After treatment.

Limitations

This study has several key limitations:

Small sample Size: With only 30 participants, the results may compromise the reliability, generalizability and statistical robustness of research findings

Short follow-up: The 6-month follow-up may not capture the long-term effects of treatment

Single-centre Study: Limited participant diversity reduces the generalizability of findings

No control group: The absence of a control group makes it difficult to draw conclusions on treatment efficacy compared to a placebo or conventional treatments

Lack of blinding: The lack of blinding in the study may have introduced bias in data collection and interpretation

Lack of standardised scoring: The absence of a universal symptom scoring system for MetS may cause inconsistencies in assessment

Uncontrolled lifestyle factors: The study did not account for lifestyle factors, which could have influenced the outcomes

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the feasibility of using homoeopathic medicines to manage MetS, particularly in individuals with elevated TG levels, and reduce cardiovascular risk, while the study provides evidence suggesting that homoeopathy may improve overall cardiovascular health, further research is needed to substantiate these observations.

Acknowledgement:

Authors express heartfelt gratitude to Dr. P. Abdul Hameed, (Professor, and HOD, Department of Practice of Medicine) for his guidance and support.

Ethical approval:

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Government homoeopathic medical college Calicut, number IEC/12/23.12.2021/24, dated 23rd December 2021.

Declaration of patient consent:

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Supplementary material available on:

https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/JISH_102_2024

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adult population in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240971.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors for metabolic syndrome in Asian Indians: A community study from urban Eastern India. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:204-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison's principles of internal medicine New York: McGraw Hill Education Medical; 2018. p. :2903-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44(Pt 3):232-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl Res. 2017;183:57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:25F-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Framingham risk score for estimation of 10-years cardiovascular disease risk in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36:36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The metabolic syndrome-A new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene-environment interaction and the metabolic syndrome. Novartis Found Symp. 2008;293:103-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The metabolic syndrome in a global perspective. The public health impact-secondary publication. Dan Med Bull. 2007;54:157-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on the role of constitutional medicine in the management of metabolic syndrome based on ATP III criteria in school-going children Kulasekharam: Sarada Krishna Homoeopathic Medical College; 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Role of Homoeopathic Medicines with Auxiliary Measures in the Management of Metabolic Syndrome among Children. Kulasekharam Sarada Krishna Homoeopathic medical college.

- [Google Scholar]

- Homoeopathic management of metabolic syndrome in children with BMI above 25. Altern Integr Med. 2022;11:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of the effects of Berberis vulgaris and its major component, berberine, in metabolic syndrome. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2017;20:557.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its risk factors in Kerala, South India: Analysis of a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192372.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome, Part 1: Worldwide definition for use in clinical practice. Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2006:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- High blood cholesterol ATP III guidelines at-A-glance quick desk reference. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/atglance.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 14]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org/a1c/diagnosis. [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 10].

- [Google Scholar]

- Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP): A marker of cardiovascular disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:240.

- [Google Scholar]