Translate this page into:

Planning for mental wellbeing in an old age home during the Covid-19 pandemic by homoeopathic institution: Structuring the intervention

*Corresponding author: Dr. Mansi Surati, Department of Psychiatry, Dr M L Dhawale Memorial Homoeopathic Institute, Palghar, Maharashtra, India. mansi.surati@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Surati M, Patel MK, Nikumbh SB, Yadav RR, Kukde AD, Nigwekar AM, et al. Planning for mental wellbeing in an old age home during the Covid-19 pandemic by homoeopathic institution: Structuring the intervention. J Intgr Stand Homoeopathy 2021;4:106-11.

Abstract

Objectives:

During the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, the risk to the mental well-being of the elderly living in an old age home (OAH) has increased considerably. Dealing with this issue requires special measures. The current literature has very few examples of such programmes. We aimed to promote emotional balance and an independent living with positive outlook on life among the residents of the OAH facility during the pandemic based on action learning principles. This programme was conducted in an OAH that our institute has been associated with for several years. HelpAge India, a non-governmental organisation working in India to assist disadvantaged senior citizens, provided a programme that covered 12 themes. This article deals with the structuring process of the programme.

Materials and Methods:

The team comprised homoeopathic consultants and the faculty and students of a postgraduate homoeopathic institute. An extensive literature search and consultation with experts from various fields enabled the team to plan and build the final programme were evolved.

Results:

Broad themes gave rise to distinct modules and objectives were derived for each of these. Detailed action plans were worked out and a plan of evaluation for each of these modules was worked out.

Conclusion:

Planning a programme to ensure well-being needs a close and accurate identification of the needs of the residents of a particular OAH. A multidisciplinary approach can help in evolving effective strategies to formulate models for geriatric mental well-being.

Keywords

Action learning principles

Patient health questionnaire:2

Generalised anxiety disorder:7

DART

Multicomponent programme

INTRODUCTION

Mental health services for older adults face significant challenges in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic as they are most vulnerable to the brunt of the pandemic. General medical complications have received the most attention in the current situation. However, few studies have addressed the potential direct and indirect effects on mental health, despite the fact that the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic (2002–2003) was associated with a number of psychiatric complications.[1] In the COVID-19 pandemic, care home residents were found to be the most vulnerable. The French Ministry of Health reported that among a total of 24,760 COVID-19-related deaths, 51% (12,511) occurred among old age home (OAH) residents.[2] Anxiety and distress, often attributed to isolation, were the most prominent mental health complaints during previous pandemics and COVID-19. In addition, post-traumatic stress was surprisingly common and possibly more enduring than depression, insomnia and alcohol misuse.[3] One likely reason for this inside OAH facilities worldwide was the lack of official guide and regulations in case of natural disasters.

The important psychosocial problems in the elderly are isolation due to sadness, wilting due to solitude, long-term illnesses leading to inactivity and abandonment by relatives. Moreover, during the pandemic, travel restrictions prevented contact between the elderly and their relatives. Outdoor activities were compromised and life was very restricted compared to earlier. All these changes make them very sensitive, often causing loneliness, depression and isolation.[4] Loneliness and social isolation are consistently identified as risk factors for poor mental and physical health in older people.[5]

HelpAge India is a non-government organisation (NGO) that works to support disadvantaged elderly people. During the pandemic, they ran a mental well-being programme in OAH facilities across the country. This programme had a fixed format and a specific number of sessions and topics. Preliminary assessment was done using the following three scales: The patient health questionnaire (PHQ:2), generalised anxiety disorder-7 item (GAD 7) and assessment of cognitive impairment through DART questionnaire. Ten general topics were suggested and it was the responsibility of the NGO to implement it in a way suitable to local conditions. Anand Vruddhashram, an OAH at Shirgaon, Palghar, which is served by the Psychiatry and Geriatric Departments of the Rural Homoeopathic Hospital, Palghar, since several years, was selected for one such programme. A series of three papers were planned on this experience. This paper outlines the processes undertaken to conceptualise and plan the programme, the second will focus on the operational issues while evaluating the results and the third will describe the benefits for the multidisciplinary team that organised the series of interventions.

Identifying relevant literature

A literature search was performed to identify activities that would aid healthy coping in the pandemic scenario. The most studies promoted group activity, including low impact exercises and creative activities such as painting, solving puzzles, watching movies with inspirational messages, connecting with others virtually, board games, yoga, meditation and mindfulness.[6,7] Certain innovative ideas such as using grounding technique, breathing techniques, the 5-4-3-2-1 technique for anxiety, as well as role playing and role reversals for imparting insight into one’s own behaviour were also reported.[8-10] The nature, type and potential effectiveness of these interventions varied greatly. Effective interventions for loneliness included psychological therapies such as mindfulness, lessons on friendship, robotic pets and social facilitation software.[11]

Four basic types of mental health models are available: Medical-psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, psychosocial and holistic-integrative model.[12] A clear delineation of the objective of enhancing the quality of life helped to choose the model that would relieve symptoms of distress, maintain mental capacities and help them to perform daily activities while adapting to age-related changes. Since their mental and physical health was negatively affected due to the social distancing, a multicomponent programme with exercise and psychological strategies to support and maintain mental health was highly recommended for this population.[13]

Challenges in designing mental well-being programs during the pandemic

Protection of the vulnerable people in the OAH was of paramount importance, especially when the medical personnel working in the hospital setting were tasked with carrying out the intervention. Online interventions were precluded due to the limited ability of the aged to relate actively to the screen as well as lack of adequate bandwidth in the rural areas.

Aim

This study aims to evolving a structure of a mental well-being programme for residents of an OAH to cater to the difficulties during the pandemic.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were as follows:

Prepare the residents of the OAH to negotiate themselves through the rigors of the pandemic

Impart awareness of their predicament and help them to accept it

Work on their coping mechanisms and strengthen them

Create an enabling atmosphere where the members can provide support to each other through establishing healthy communication

Empower the caretakers of the home to discover their potential without compromising on their caring function

Ensure that all the interventions are action based and not merely imparting facts to be imbibed passively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study

A mental health intervention in an old age facility.

Subjects

Twenty-four senior citizens of the Anand Vruddhashram (age range 62–89 years; 11 men and 13 women).

Study setting

The Anand Vruddhashram OAH at Shirgaon, Palghar.

Methodology

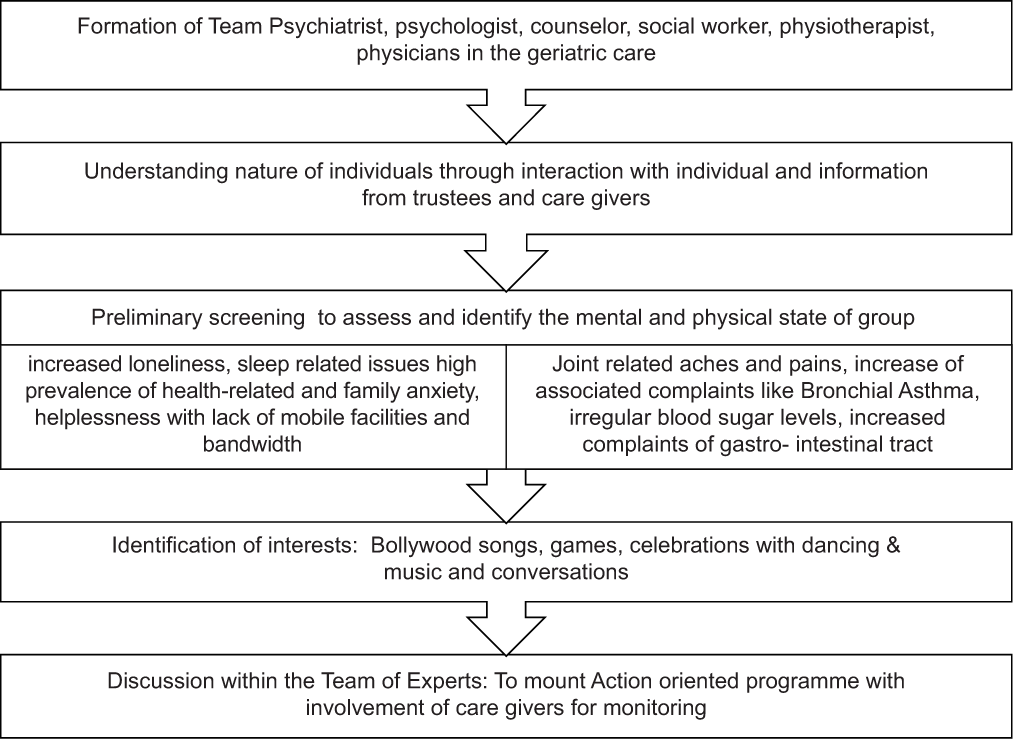

The flow diagram indicates the steps followed for structuring the programme.

Evaluation

Evaluation was planned at intervals of 3 months. Method of evaluation:

Observation of behaviour

Observation of care givers

Talking to the trustees

Involvement of group in workshops that were used as a guide to plan further workshops.

Objective evaluation at the end of the programme was through the use of scales (PHQ:2, GAD:7 and DART) for post-assessment.

RESULTS

Nature of the individuals/group

The preliminary screening allowed us to understand the individuals and the groups as follows:

The group was socially heterogeneous: People from the upper and middle classes as well as some homeless individuals were living in the OAH. Some had owned businesses, some had had a job and some struggled to earn money and survived through odd jobs

The temperament of individuals differed widely: Aggressive egoism, dominant anxious, timid introvert and friendly extrovert. Handling each of them and involving them in each workshop was a challenge

Since backgrounds were different, there was heterogeneity in language issues as well. Some preferred Marathi, some Gujarati and some Hindi. Few had hearing difficulty, which also demanded personal attention during conducting the workshop

There was already some groupism and interpersonal issues as well as considerable difference in choices and interest in general. The programme was supposed to balance the sensitivities and bring positive change in environment.

Structure of planned modules

The detailed structure of the modules evolved through consideration of the objectives and the character of the individuals and the group as a whole is reproduced in [Table 1].

| S. No. | Module | Objectives | Nature of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understanding mood | 1. To understand one’s own emotion and mood 2. Impact of emotions on behaviour 3. Identifying thinking processes responsible for mood. |

Ice breaking activity – assessing current mental state based on thought processes and building discussion on same. This would benefit in engagement of group and to build discussion Activity – showing a relatable movie preferably without a dialogue that inspires the group to lead an independent life in their old age Followed by discussion and take-home. Audio – Bhajan giving direction to life. |

| 2 | Handling anger and frustration | 1. Understanding anger and its expression at mind and body 2. Identifying impact of anger in daily routine |

Role play by team demonstrating different shades of anger. Followed by group discussion on identifying anger and its impact on mind and body Relaxation exercise – group chanting ‘OM’ |

| 3 | Emotional well-being | 1. Enable them to identify one’s own mood 2. Demonstrate techniques to deal with one’s own emotional state |

Self-evaluation of emotional well-being – for insight into one’s current emotional state Using PowerPoint to determine the impact of various images on mood. Showing a movie to lift their spirits Group activity – demonstration of simple techniques to deal with anxiety Self-assessment of mood at end of session |

| 4 | Handling fear and anxiety | 1. Awareness of anxiety and its expression 2. Understanding bodily expressions of anxiety 3. Diluting denial of experiencing fear and anxiety |

Pre-decided role play by residents indicating behaviour out of fear and anxiety. Inviting solutions from group itself. Relaxation exercises Use of music as a stimulus to handle agitation Action plan: Playing relaxation music at time of breakfast, lunch and dinner. Monitoring to be done by caregivers and trustee |

| 5 | Identifying depression | 1. Awareness about depression in older people 2. Identifying expressions of depression in older people 3. Learning to deal with depression through group activity |

Pamphlets of emoticons – exercise to identify the expressions of partner resident Colouring of emoticons was to be done – one copy for self and one for partner Filling colours in emoticons: Discussion on reasons for colour selection and multiple strokes Using scale for the assessment of loneliness and boredom Correlating outcomes of both activities Conclusions and take-home |

| 6 | Forgetfulness and dementia | 1. Identifying difference between age-related forgetfulness and dementia | Session by subject expert clinical psychologist. Highlighting difference between forgetfulness and depression through examples Discussion on daily life examples of forgetfulness and its causes Physical exercises to enhance intellectual functioning |

| 7 | Being physically active | 1. Importance of physical exercise 2. Its impact on mental well-being |

Session by subject expert physiotherapist Discussion on importance of physical exercise on mental well-being Group activity: Exercise in sitting postures Encouraging residents to attend physiotherapy sessions on regular basis |

| 8 | Art of graceful ageing | 1. Encouraging concept of graceful ageing 2. Accepting ageing wholeheartedly as natural process |

Selection of a video depicting graceful ageing – for example, age is a number, young heart – aged body, youthful life at old age, life advice from opposite poles of life Sensitive discussion on bringing grace in life |

| 9 | Power of meditation | 1. Sharing importance of meditation 2. Encouraging to include meditation as part of daily routine |

Delivering concept of meditation in wider perspective: Various ways of meditation Group activity of meditation |

| 10 | Group dynamics | 1. Enabling them to consciously identify the bond they share as a group | Discussion – reviving memories and positive experiences from residents and support from caregivers Action plans on the way ahead |

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the critical importance of community services to support health and social care for the ageing population. Community organisations are noting mental health challenges for people experiencing social isolation and stress. Meeting interrelated health and social needs will require sustained efforts by health care and social care providers.[14] One such study was conducted in Israel to promote positive ageing through practical approaches. Skill training interventions with educational and behavioural components had a significant effect on positive mental health outcomes. Their methodology focused on senior citizens developing positive attitudes toward ageing by making them review their past accomplishments and their current resource and strength. Various positive psychology strategies were used in sessions enabling them to explore personal strengths, practicing ways to use them and invest in significant relationships, keeping a gratitude diary, listing the good things that occurred in a day, practicing mindfulness, seeking out activities to create flow and appreciate learning experiences from their very own stories to live with hope.[15] In contrast, in our study, we focused on improving quality of life based on behaviour modifications applied through action learning principles. These interventions included meditation, chanting, physical exercise, relaxation exercises, role playing to develop insights through psychoeducation by making them identify their own maladaptive behaviours and group discussions to modify the same. A study by Beauchamp et al., a randomised control trial, reported an online delivered group and personal exercise programme to support less active older adults. The 3-way parallel study was to assess whether group-based exercise versus personal and wait list control (WLC) help to improve psychological health. The participants in the personal condition displayed improved mental health compared to WLC participants, in the same medium effect size (ES) range (ES = 0.293–0.565) over the first 8 weeks, and while the effects were of a similar magnitude at weeks 10 (ES = 0.455, P = 0.069) and 12 (ES = 0.258, P = 0.353), they were not statistically significant. The study indicated the need for a more holistic mental well-being programme with personal engagement and involving caregivers for monitoring.[16] However, our study included a team of experts in various subjects and topics of workshop, which makes its approach more holistic. The methodology included personal connections with residents and involvement of caregivers and trustees of the OAH for monitoring, regular documentation and communication within the team, which was one of the key factors making the programme more holistic and linked. The preliminary processes of screening, knowledge of the background, interests and temperament of the residents helped to a great extent to cater to their needs. Knowing the residents’ interest areas helped identify the mode of conduct and need to deliver based on action learning principles. We shall present the results of our interventions in the next article of this series.

Any modifications in patterns of thinking, feeling and action were brought out through experiential learning, since the group had little interest in reading and knowledge-based interventions. Hence, the mode of intervention planned was discussion and activity based. Adopting the suitable mode would invite interest and foster group engagement. Few sessions were to include videos, short movies and music where messages were conveyed through entertainment. We attempted to demonstrate simple techniques that could be easily adopted and be made a necessary part of daily living.

Since the psychosocial aspects of older people, their caregivers, psychiatric patients and marginalised communities are affected by this pandemic in different ways, there is an urgent need to develop psychosocial crisis prevention and intervention models by the government, healthcare personnel and other stakeholders.[17]

CONCLUSION

Understanding the needs of residents of OAH facilities play an important role in planning interventions. Activity-based interventions that ensure wide participation can imbibe dynamism in the group. A readiness to improvise with changing time and circumstance always needs to be kept in mind. Regular and open communication fosters trust and forges strong bonds. Each OAH is different in its composition, history and ethos. Identifying these and selecting suitable strategies play a key role.

Considering the limited possibilities of direct interventions in the pandemic, the project is unique considering the structure and planning required for implementation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Valerian Pais, Deputy Director Programme, Maharashtra – Goa territory and Mrs. Kamla Shrivastava, Deputy Director Fundraising, HelpAge India, for giving us an opportunity to structure and implement these workshops over a period of 3 months. We thank the trustees of the Anand Vrudhashram, Shirgaon, Palghar, for permission to conduct the workshops. We also appreciate the consistent engagement of our postgraduate students, Dr. Tanveer Sheikh and Dr. Natasha Naidu for being part of the workshops.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

The programme was funded by HelpAge India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Covid-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on long-term care facilities worldwide: An overview on international issues. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8870249.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planning for mental health needs during COVID-19. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Video calls for reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD013632.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oceans Healthcare. 2021. Available from: https://oceanshealthcare.com/news/165/8activitiestoboostmentalhealthforseniorsduringthecovid-19outbreak [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- The State of Queensland; You've still got it: 10 Activities for Boosting your Mental Wellbeing Later in Life. 2020. Queensland Health. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/news/mental-wellbeing-health-older-senior-queenslanders-tips-activities [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 23]

- [Google Scholar]

- 5-43-2-1 Coping Technique for Anxiety. 2021. BHP Blog Behavioral Health Partners. Available from: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/behavioral-health-partners/bhp-blog/april-2018/5-4-3-2-1-coping-technique-for-anxiety.aspx [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 23]

- [Google Scholar]

- Relaxation Techniques for Stress Relief. 2020. Available from: https://www.helpguide.org/articles/stress/relaxation-techniques-for-stress-relief.htm [Last accessed on 2021 Sep 02]

- [Google Scholar]

- Grounding techniques: Step-by-step guide and methods. 2020. Medical News Today. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/grounding-techniques [Last accessed on 2021 Sep 02]

- [Google Scholar]

- Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 physical distancing measures: A rapid systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0247139.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A new geriatric mental health outreach model of care for residents of long term care facilities; results of a continuous quality initiative. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2015;4:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:938-47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To support older adults amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, look to area agencies on aging. Health Affairs Blog. 2020;2020:928642.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fostering well-being in the elderly: Translating theories on positive aging to practical approaches. Front Med. 2021;8:517226.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Online-delivered group and personal exercise programs to support low active older adults mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e30709.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:779-88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]